On February 2, Apple’s first mixed-reality headset, the Vision Pro, officially launched, with a release event held in New York at 7 a.m. that day. Apple has called this product its most significant innovation since the iPhone’s debut in 2007, heralding a new era of “spatial computing.” Since preorders began on January 19, over 200,000 units had been sold by the end of January.

As a groundbreaking hardware platform distinct from PCs and smartphones, the Vision Pro has more than one million apps available in its dedicated App Store even before its official release. Its expansive virtual screen, 3D interface, and interactions via eye tracking, gestures, and voice commands promise to redefine how users work and play. However, these cutting-edge features rely heavily on a diverse array of sensors collecting personal data, raising significant privacy concerns among industry experts.

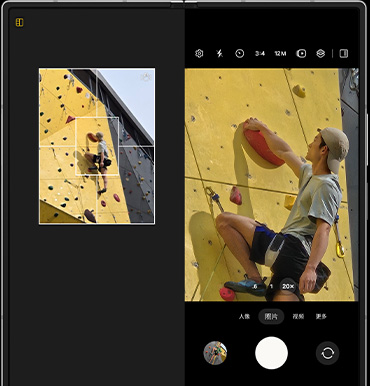

Equipped with two depth sensors, 12 cameras, and six microphones, the Vision Pro introduces a new level of privacy and security risks compared to traditional smart devices. How does the Vision Pro alter the privacy landscape for wearable devices, and what unique challenges does it present?

Promises and Concerns

Compared to previous devices like computers and smartphones, the Vision Pro’s increased number of sensors and features make managing its data collection and privacy protection much more complex.

Cai Yong, co-founder of the internet security organization “Cyber Blade,” highlighted three major privacy risks posed by the Vision Pro:

- Sensor Exploitation Risks: The numerous data-gathering sensors offer attackers multiple entry points for exploitation.

- Media Sharing Risks: With multiple cameras and microphones, the Vision Pro increases the likelihood of privacy breaches during activities like live streaming or sharing media.

- Data Security Risks: The data scanned and collected by the Vision Pro could include sensitive information, which, if inadequately protected, might be stolen or accessed without authorization.

For the first two concerns, Apple has implemented measures in the Vision Pro’s design. For instance, an indicator light illuminates when the Vision Pro is capturing spatial photos or videos, notifying those nearby.

However, the risks tied to data security remain a hotly debated topic. The Vision Pro collects and processes sensitive personal data, such as eye-tracking information and spatial environment details, which carry commercial value. Under personal information protection laws, such data—classified as sensitive personal information—includes biometric data and location tracking.

Cai Yong noted that data like gaze duration could reveal user attention patterns in specific environments, which is often used for targeted advertising and product optimization. Meanwhile, environmental data, including user location and climate conditions, could be analyzed for market trends or location-based advertisements.

Apple’s official information indicates that Vision Pro users’ browsing and eye-tracking data will not be shared with Apple, third-party apps, or websites. Additionally, Apple has developed Optic ID, a new security authentication system based on iris recognition. Optic ID uses invisible LED light to analyze the uniqueness of users’ irises, enabling quick device unlock, Apple Pay authorization, and password autofill. The data is fully encrypted and stored locally, never on Apple’s servers or accessible to third-party apps.

Still, as much as Apple promises to safeguard user privacy, verifying the company’s adherence to these commitments remains challenging for individual users.

“As an individual, it’s difficult to verify the reliability of Apple’s claims about protecting eye-tracking data,” Cai Yong explained. “This is because Apple controls and implements the data protection measures, leaving users unable to directly audit how their data is handled and shared.”

For now, users can only rely on conventional privacy protection methods: carefully reading privacy policies, keeping software updated, and managing app permissions.

Emerging Risks with Wearable Devices

As wearable devices continue to enhance sensory interactions, the risks associated with the personal data they collect remain a growing concern. The Vision Pro is not an isolated case. Back in 2013, the introduction of Google Glass sparked similar fears about privacy breaches from its cameras and small display. In one U.S. survey, 72% of respondents cited privacy concerns as their reason for rejecting Google Glass.

Governments are also tightening regulations on smart wearables. In China, for example, authorities flagged several wearable apps in 2021 for collecting unnecessary personal data unrelated to their services.

Wearable devices often require sensitive personal information to function effectively, such as location data, health metrics, and activity history. Under personal data protection laws, companies must adopt stringent safeguards when handling sensitive information. Striking a balance between data collection and user privacy remains an ongoing challenge as technology evolves.

Not all risks have garnered widespread attention. For instance, a 2023 study revealed that head and hand motion data alone could uniquely and consistently identify about 55,000 VR users. This highlights a lesser-known vulnerability of wearable devices.

Devices like VR and XR headsets have not alleviated privacy concerns over the years. For instance, Meta’s Oculus Quest 2 faced criticism for violating child safety regulations. Several harassment incidents involving minors occurred in VR Chat, Oculus’s popular social app, exposing vulnerabilities in protecting sensitive personal data and safeguarding vulnerable groups.

As the Vision Pro ushers in the era of “spatial computing,” it represents a technological leap forward. However, the challenges it introduces regarding personal data protection demand careful and continuous scrutiny.